On April 3, it was finally supposed to be over. After a nine-week trial, a jury in Melbourne found Malka Leifer, 56, guilty on 18 counts of sexual assault, including five of rape, of two teenage girls who had been in her charge as principal of the ultra-Orthodox Adass Yisrael School. It seemed like the long-awaited end of a 15-year saga that began when Leifer fled to Israel and the Australian Jewish News (AJN) stunned the community by breaking the story.

But it wasn’t over. Sisters Dassi Erlich and Elly Sapper, who chose to identify themselves publicly, had been vindicated in court (Leifer was found not guilty of assaulting a third sister). But the accusations kept swirling. Two months after the verdict, the police confirmed they had reopened an investigation into those at the school who allegedly helped Leifer evade justice back in 2008. She had fled to Israel on a plane ticket purchased by others on the same day she learned of the allegations.

Every crime of this nature ripples out in shockwaves, leaving a range of casualties in its wake. Families are torn apart, institutions shaken, communities damaged. In the case of Malka Leifer, the damage extended nearly halfway across the world.

When I landed in Melbourne some months back, I had hoped to catch a session at the opening of the Leifer case, but it had been delayed. It was my second trip to the city, and it struck me on both visits that Melbourne’s is as close to a model Jewish community as you can get. Its size (nearly half of Australia’s estimated 120,000 Jews live there) and its isolated location have bred unique self-sufficiency and strong communal organizations. The rate of intermarriage is relatively low compared with that in other Western Jewish communities. An influx of South African Jews over the past few decades has also boosted its numbers. On the other hand, the fact that the Australian Jewish population is not that large has made the community outward-looking, and it maintains strong relations with Israel and other Diaspora communities.

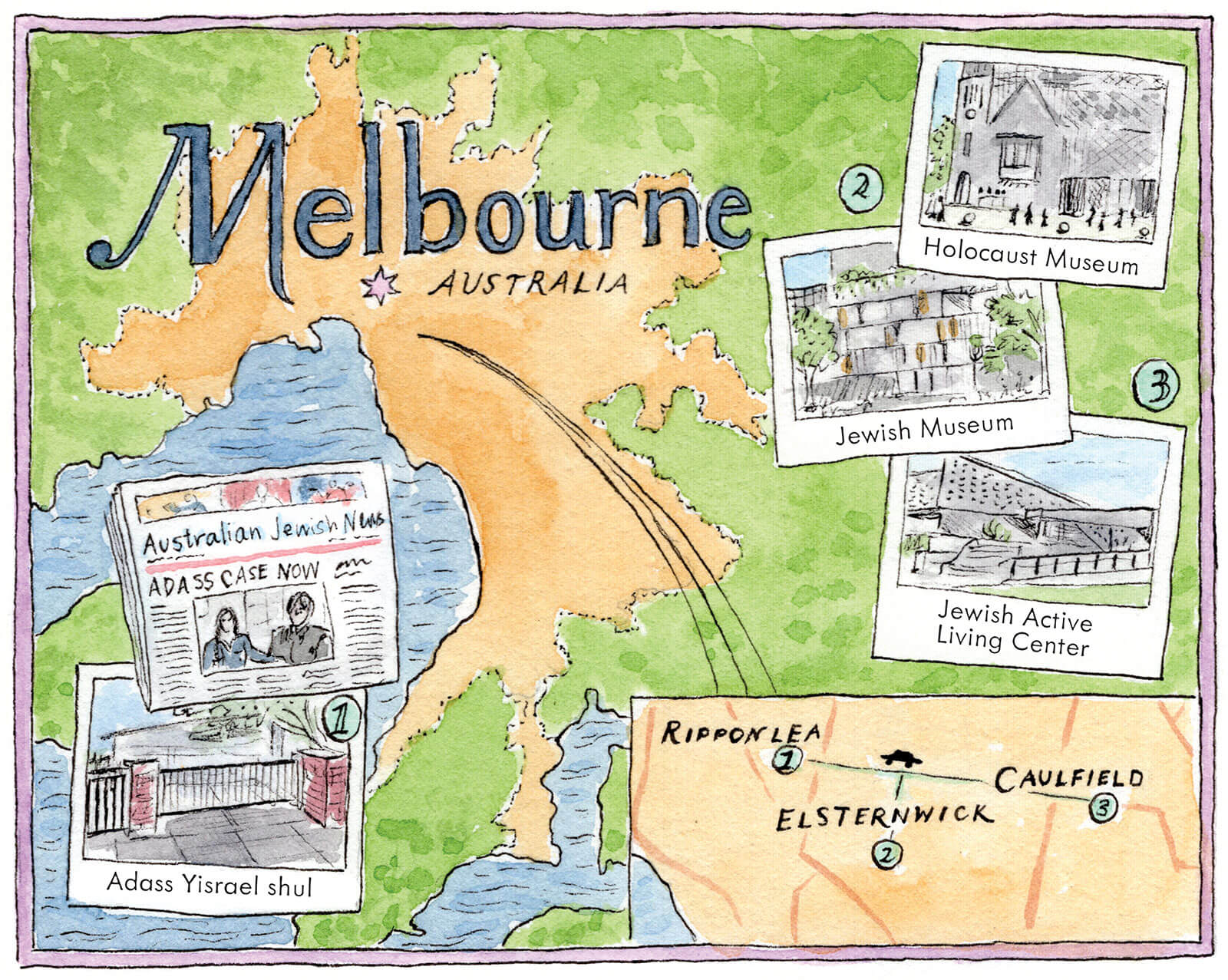

In addition, the community’s relatively short history means that a large proportion still identifies not just as Jews, but as specific types of Jews. Walk for just a quarter of an hour across Elsternwick and Caulfield, the southern suburbs where most of the Jews live, and in quick succession you’ll pass shuls and day schools, youth and community centers, of nearly every denomination of Judaism: Hasidim, including Chabad, Litvaks, the various stripes of non-Haredi Orthodoxy, progressive and secular Zionists, all the way to non-Zionist neo-Bundism. All kosher services offered. Every flavor of Jewish culture available homegrown or imported. A community large and affluent enough to supply it all, but too small to break up into separate sects.

I’m sure some Australian Jews reading this will dispute this sunny appreciation of their community and point to problems and shortcomings. But I have traveled widely across the Jewish world, and there is nothing like Melbourne. Where else in the rapidly polarizing Jewish world is there a major community where religious and secular, left- and right-wing Jewish youth movements, go together to summer camps and joint study on Shavuot night? They also run some of their Israel programs together.

But the best proof of its strength is the way it handled the Leifer case. It was a mainstream Jewish newspaper, the 128-year-old AJN, that broke the story in 2008. It was the community that kept up the campaign to support the victims, including a tenacious lobbying effort to pursue Leifer’s extradition after she had fled to Israel. And despite the powerful feelings that such a case inevitably evokes, Melbourne’s Jews also ensured there was no ugly backlash against the Haredi community.

“There was some pushback, and people writing in that we shouldn’t have published the story, that it would fuel antisemitism and should be dealt with internally,” says Ashley Browne, who edited AJN at the time alongside his deputy Naomi Levin. “But there was also a lot of support and I think a broader consensus that what we were doing was vital.” In the week after first running the story, the AJN published letters attacking it for committing the sin of lashon hara (gossip).

But as time has passed, it has become much rarer to hear that line of criticism.

The saga of Leifer’s escape to Israel and her lengthy extradition case also put a strain on Australian Jewry’s strong ties with Israel. Those ties had been tested before: in 1997, when four members of the Australian delegation to the Maccabiah Games died because of the catastrophic failure of a shoddily built pedestrian bridge, and again in 2010 with the suicide in an Israeli prison of Ben Zygier, a Melbourne-born Mossad agent. But the Leifer case — unfolding in locations 8,500 miles apart, from Australian courtrooms, to the Haredi towns in Israel where Leifer sheltered, to the therapist’s office in Israel where Dassi Erlich began speaking about her ordeal after making aliyah — was in a different league.

There aren’t many Diaspora communities, including in the United States, that can engage effectively with the often-cumbersome Israeli legal system. Melbourne’s engagement went all the way to Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Netanyahu promised in multiple meetings to solve the crisis, but he failed to publicly reprimand his Haredi health minister, Yaakov Litzman, for pressuring the district psychiatrist for an assessment that Leifer was unfit to be extradited to Australia to stand trial. Nevertheless, Litzman ultimately admitted in a plea deal to using his ministerial power to help shield Leifer.

Beyond the challenge of dealing with the Israeli government, there was the equally difficult task of bridging gaps between Melbourne’s wider Jewish community and its insular Hasidic community, many members of which are descended from Hungarian Jews who arrived after the Holocaust.

That’s clearly visible within a few street blocks in the small neighborhood of Ripponlea. The Adass Yisrael shul and the separate boys’ and girls’ schools nearby look nothing like the wide and welcoming campuses of Melbourne’s other Jewish institutions. There are no distinguishing signs on the buildings, the entrance is through side doors with keypads and CCTV, and the children play in tight courtyards behind tall fences. I went inside the shul to daven mincha, and the men there were friendly enough, but nobody wanted to talk.

The Hasidim here are not affiliated with a particular Hasidic court, but are called klal-hasidi, or general Hasidic. Even within them there are schisms. Around the corner from the main shul is a tiny offshoot minyan that insisted on continuing to gather for prayer during the pandemic, despite the strict lockdown and social-distancing regulations. On its unobtrusive door there’s a tiny handwritten notice in Hebrew quoting Genesis 19:11: “They were helpless to find the entrance” — a sly reference to the depraved residents of Sodom, struck blind when they tried to break into the house of Abraham’s nephew Lot to seize the angels sent to save him.

Down the street there are a handful of kosher groceries and butchers. “We’re a separate community, but we do a service to the non-Haredi community by providing most of the kosher food and catering,” says one patron who asked not to be named. “They did us a service with Malka Leifer. Everyone knows she did terrible things, but our community can’t handle these things.”

“Our Shoah legacy is important, but there’s a feeling that for Adass it’s ever-present and still dictates much of their relationship with the outside world,” one Jewish educator told me. “And there is a general tendency of protectiveness toward Adass, despite the criticism of their conduct during Covid and over Leifer.”

Speaking with various Australian Jews, I heard some level of understanding for the Haredi trauma at the very idea of a member of their community, especially a woman, being in prison among the goyim — not that this understanding extended to any kind of sympathy for Leifer, of course.

There are also notes of criticism of the Melbourne Jewish community’s leadership: that it was perhaps easier for them to confront a scandal originating in a school none of them had any responsibility for or affiliation with; that, had the three sisters not gone public, the story might have been swept under the rug; that some of the impetus to deal with the scandal owed something to the wider coverage in the Australian and international media of sexual abuse in the Catholic Church.

Still, it is very easy to envisage how it all could have resulted in very ugly scenes of Haredi-bashing, Israel-bashing, and a breakdown of relations between the Jewish community and the police. None of that happened.

The Leifer case and the experience of Melbourne Jewry highlights questions crucial to the relationships between Jewish communities in Israel and the Diaspora, and with the wider world. The responsibility for the welfare and education of children in ultra-Orthodox schools has in recent months become a major political issue throughout the Jewish world. That’s true in the city and state of New York, where Hasidic schools have been the subject of a controversial series of investigative pieces in the New York Times. It’s true in Britain, where the national inspectorate of schools and childcare, OFSTED, has been clashing with the ultra-Orthodox community. And it’s true in Canada, where former Hasidim have taken the government of Quebec to court, claiming that they fail to supervise Haredi schools.

It is an acute dilemma for Jewish leaders and senior professionals in Israel and the Diaspora, who must engage with growing and increasingly influential Haredi groups that are not part of the general communal framework. Matters haven’t been helped by the political situation in Israel, where the ultra-Orthodox parties are key members in Netanyahu’s coalition, which now confronts a largely secular Israeli middle class bitterly opposed to the government’s attempts to overhaul Israel’s judiciary.

Does the wider Jewish world have a duty to care for individuals, especially minors, within Haredi communities and schools? And if so, does that extend just to cases of sexual abuse or also to the curriculum? When Haredi institutions clash with local and national governments over such matters, should the legacy Jewish establishment weigh in? And on whose side?

There are no easy answers. Cooperation is crucial. In some places, there has been progress on matters such as adult education and vocational training, but levels of suspicion have never been higher. As the leader of a major American Jewish organization who works closely with Haredi counterparts says, “you are constantly being scrutinized for any sign of enticing Haredim to leave.”

Do Melbourne and the Leifer case offer some answers? The renewed investigation may yet plunge the community into recriminations. But Jewish leaders would do well to take note of how the Jews Down Under dealt with this crisis.