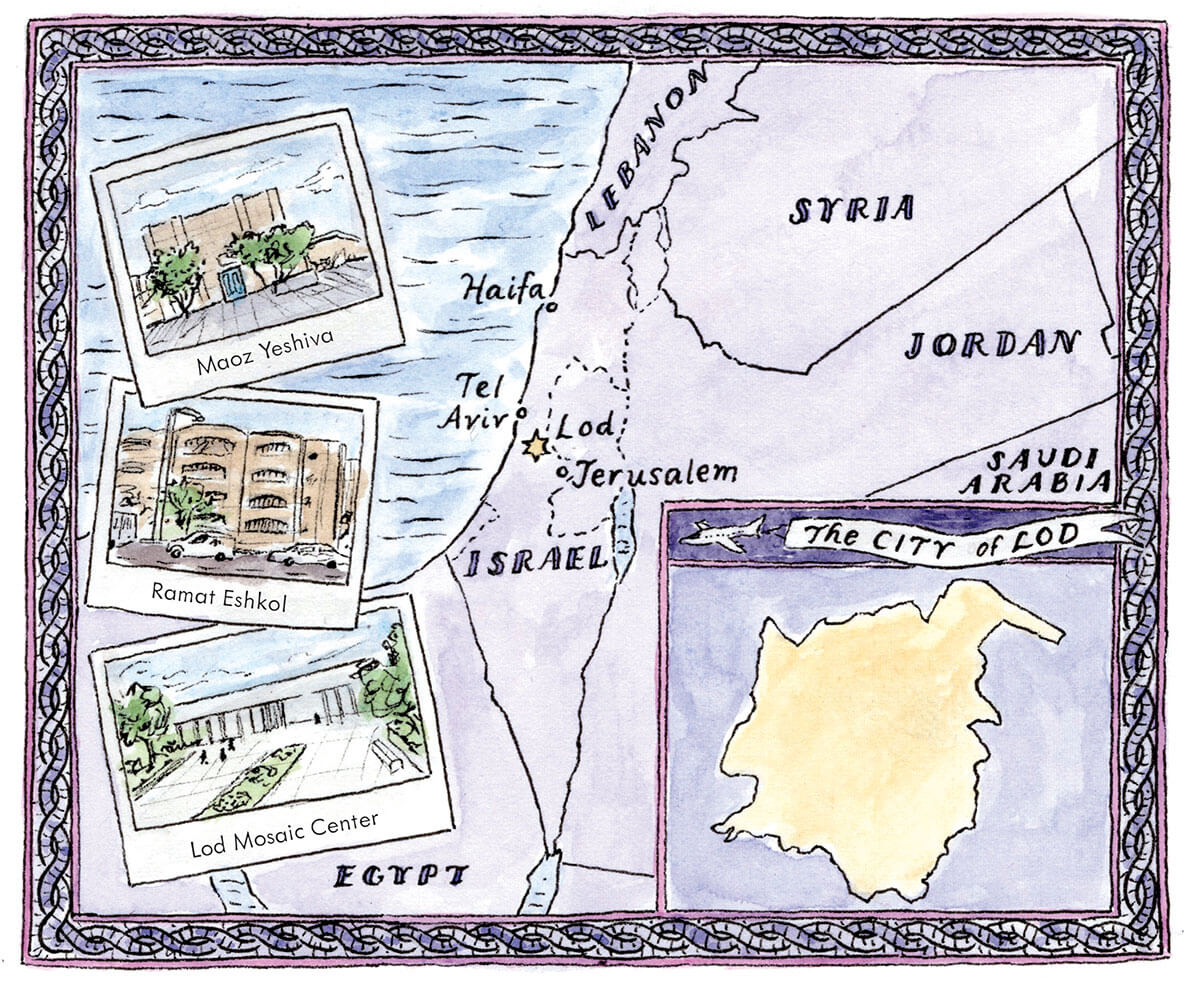

The 1,700-year-old Roman mosaic, discovered in 1996 at the end of a street in Lod, is one of the largest and best-preserved mosaics ever discovered in Israel. Dozens of land and sea animals cavort across its tiles. Indeed, it is so magnificent that the Shelby White and Leon Levy Lod Mosaic Center was built around it.

The museum also contains a small exhibit dedicated to the 8,000 years of continuous human habitation of Lod. On the last frame, the caption reads, “During the War of Independence, the city was captured and many of its Arab inhabitants fled. In the 1950s, thousands of new immigrants settled in the city, and Lod became a mosaic of ethnic and religious groups living side by side.” The last major event to take place in this city of 85,000 — three-quarters Jewish, the rest Muslim or Christian Arab — was the outbreak in 2021 of rioting in which the mosaic museum was one of the targets. But it is not mentioned there.

Leaving the mosaic museum, you turn right onto He’Halutz Street. If you ignore some roosters and ducks wandering on the pavement, most of the street seems a normal, though rather rundown, Israeli shikun — a building project.

There are two public buildings on He’Halutz (which becomes Exodus Street), though you wouldn’t expect to find them on the same street of an Israeli city. One is the Al-Razi Elementary School, the sign outside in Hebrew and Arabic denoting that this is an official Israeli state school serving the Arab community.

A bit farther down is the Maoz Yeshiva pre-military academy, where about 40 high-school graduates study Torah and undergo physical training for a year before they enlist in the IDF’s combat units. The fences around Maoz are festooned with large Israeli flags. A new outdoor gym is dedicated to the memory of Noam Raz, a member of a counterterror unit killed in 2022 in an operation against Palestinian terrorists near Jenin. At the end of the street, you arrive at the bustling open-air market in the center of old Lod.

There’s a parallel street connecting the museum and the market. It’s named for Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, the visionary who devoted his life to reviving ancient Hebrew. Yet on the Lod street bearing his name, all the signs in Hebrew have been removed from the houses, replaced by green-and-white signs in Arabic. Another nearby school, this one run by a private Christian foundation, posts its signs in Arabic and English. It’s as if Israel doesn’t exist on this street.

Welcome to Ramat Eshkol, the most explosive neighborhood in Israel. These are the streets where the rioting that swept Israel’s “mixed” cities in May 2021 broke out.

Most of the shoddily built four-story apartment blocks were built for the families of Jewish immigrants who had arrived in Israel from North Africa in the 1960s and later from the Soviet Republic of Georgia. As tourism expanded, many were employed in menial jobs at nearby Ben Gurion Airport. But the neighborhood was never an attractive place to live, and when the new towns of Shoham and Modi’in were built in the early 1990s, there was a mass exodus from Exodus Street.

In their place came two groups. One consisted of Ethiopian Jews who had arrived in Israel a few years earlier with no property of their own. The others were Arab families, mostly the descendants of 1,000 or so essential employees of the Palestine Railways company who had been allowed to remain in the city when the rest of the 20,000 Arab residents were forced by the IDF to leave after the city’s capture in July 1948.

Within the space of a few years, Ramat Eshkol had an Arab majority. In a remarkable historic turnaround, the Weizmann Elementary School, almost emptied of pupils, became the Al-Razi School.

Ramat Eshkol was never an attractive place to live, and when the new towns of Shoham and Modi’in were built in the early 1990s, there was a mass exodus from Exodus Street.

The last time I’d been to Ramat Eshkol was on the second day of clashes in Lod. I’d arrived in the morning when most of the rioters were sleeping off the previous night’s mayhem. There were squads of Border Police stationed in the neighborhood, but they didn’t seem enough to quell another night of violence. By then, the rioting had spread to a dozen other locations across the country, and a 12-day war against Hamas in Gaza had begun.

I parked next to the deserted market square, mindful of dozens of burnt and still-smoldering vehicles in the parking bays beside me. The upper floor of the small municipal office was also burnt out, as were a few windows of apartments facing the market. “Our neighbors knew exactly which cars and apartments belonged to Jews,” one of the Jewish residents told me.

The police were hunkered down in their armored vehicles. The only other people were a group of young Arab men lounging on the other side of the square while one of them did doughnuts in the square with an old Honda. Perhaps they were just tired, or maybe it was the low-grade weed they were smoking, but they were happy to talk. They didn’t try to deny they had been among the rioters the previous night.

But why?

The imams had called them out to protest “the Jews defiling al-Aqsa.” But for most of them, it wasn’t about what had been happening on the Temple Mount. They had never even been to Jerusalem, one admitted, in perfect Hebrew. It was about life in Lod.

“It’s only 20 percent about religion,” said one. “And it’s not really about the Jews here either, some of them are our friends. But the police and the city council have been oppressing us, arresting every kid who sets off fireworks on Ramadan, forcing the mosque loudspeakers to turn down their volume, and demolishing buildings they say were built without a permit. There’s so much pressure and poverty here that it was going to burst at some point like a balloon. Al-Aqsa was just the spark.”

Every Jewish voter I met said that they voted for Religious Zionism ‘out of recognition of what they had done for us during the riots.’

“How do you expect us to calm down when the police come here only when the victims are Jews?” said another. “When an Arab murders an Arab, they come the next day, arrest a member of each family, and then release them for lack of evidence.”

As I was leaving Ramat Eshkol on that second day of rioting, a convoy of private vehicles had drawn up outside the Maoz academy, which, along with a number of shuls, had also been the target of arson attacks during the night. Groups of Jewish men, many armed, were disembarking. It was a motley group of settlers, recently discharged soldiers, far-right activists, and members of the racist “La Familia” ultra-supporters of Beitar Jerusalem Football Club. All were coming in response to appeals from the Jews of Lod for protection.

Not all the Jews in town were entirely happy to see them. “I personally had to check each of them, and there were those I told to leave,” says Noam Dreyfuss, the CEO of Lodaim, an organization representing Dati-Leumi (National Religious or Modern Orthodox) families who started to come to and live in the town over the past 20 years. “But the bottom line is that they came here when we needed them, and it was the MKs [members of Knesset] of Religious Zionism who helped to organize them. Which is one of the reasons many people here voted for them.”

Lod has for decades been a Likud stronghold, and the party came first as usual in November’s elections. But its showing this time was relatively weak. Only 28.5 percent of Lod citizens voted for Likud, significantly under the 34.3 percent it took just 20 months earlier in the March 2021 election. More intriguing were the parties that came in second and third place.

Balad, the most nationalist of the Arab-Israeli parties, won 15.7 percent of the Lod vote. Another 15.5 percent of the city voted for the far-right Religious Zionism list. In other words, nearly a third of Lod’s residents voted for the most radical Jewish and Arab parties on the ballot in the last election.

Every Jewish voter I met said that he or she voted for Religious Zionism “out of recognition of what they had done for us during the riots.” So did Dreyfuss, who stressed that he aligns himself with the more religious wing of the list, led by Bezalel Smotrich, rather than with Itamar Ben-Gvir’s Jewish Power faction. The vote for Religious Zionism in Lod is significantly higher than its national share of 10.8 percent, but the doubling in its strength from the previous election is actually identical to RZ’s growth nationwide.

The change in the Arab vote in Lod is more ominous.

Three Arab-Israeli parties ran in this election. Ra’am, the Islamist-conservative party that had been in coalition with the government of Yair Lapid and Naftali Bennett, won the most votes nationwide, followed by Hadash-Ta’al, who are less enthusiastic about joining an Israeli coalition but do not rule it out. Balad, by contrast, is opposed to any cooperation with a sitting government as long as Israel regards itself a Jewish state. It came last among the three in the election, with only 2.9 percent of the nationwide vote, failing to cross the threshold needed to win seats in the Knesset.

In other words, Balad won just a quarter of the votes cast for Arab-Israeli parties nationwide. But in Lod it won three-quarters.

“I wouldn’t read too much into the result,” says Fida Shehade, a city planner, prominent Arab activist, and until recently a member of the town council. “Don’t forget that Sami was born in Lod and he has a lot of family here,” she adds, referring to Sami Abu Shehadeh, the party’s leader. “The Arab vote is primarily tribal. But also it’s a rejection of the establishment. People didn’t want to vote for Ra’am because there’s a feeling that the Jewish center-Left just used us to bring down Netanyahu, and for Hadash who were always the largest Arab party and too complacent. Here in Lod at least, we saw Balad people working hardest and voted for them.”

But what does the vote say about the future of Lod?

Based on its location alone, Lod should be one of the most desirable places to live in Israel. “For people like me who really don’t like Tel Aviv but need to be there every day for work, Lod is almost ideal,” says the founder of a tech company who lives in the city. “I have a great community here as well. But the violence, not just last May but also on a daily level — robberies, fires, people, usually Arab youths, hitting kids or sexually harassing girls on the street — makes me wonder if there’s a future here.”

Lod’s greatest asset — being an affordable and accessible town at the intersection of Israel’s two main highways — is also its biggest drawback. Whether by design or coincidence, it has become the place where a wide variety of “outsider” communities have sprung up. There is a neighborhood of Palestinian “collaborators” who fled their homes in the West Bank and were allowed to settle in Lod. There is a Bedouin community from the south. There are large groups of foreign workers, from dozens of countries, employed in Tel Aviv.

Most people I spoke to in Lod after the election, both Jews and Arabs, were pretty certain that another round of rioting, like the one last May, wouldn’t break out. But not necessarily for positive reasons.

It hasn’t helped that the city has had a weak and inept leadership, and in many cases the central government had to step in and appoint a mayor from outside. The current mayor, Yair Revivo, has been in office for nine years. He has persevered largely because he has succeeded in pushing new building projects in the southern part of the city, which is predominantly Jewish. The older neighborhoods in the central and northern parts, where most of the Arab and the poorer Jewish communities live, remain dilapidated.

In these areas however a new community has built its home: the garin torani.

A garin, not a word easily translatable into English but familiar to anyone with a background in Jewish youth groups, is a group of young people with a mission. In this context, the garinim toranim are groups of young religious couples who have made their homes in Israel’s development towns and less desirable working-class areas. Their mission is the building of God-fearing Zionist communities. In some towns, they have been credited with boosting local society, but they are often accused of elitism. In mixed towns such as Lod, they are viewed by the Arabs and some of the Jews as settlers.

Lod’s garin torani was founded in the mid-1990s. Today it is the largest of the garinim, with nearly a thousand young religious families. Because of the city’s circumstances, it is also the most controversial. Its members prevailed on the Housing Ministry to build an exclusively Dati-Leumi neighborhood, Ramat Elyashiv, in the old center of the city, just next to a predominantly Arab area. In recent years, more of its members have been moving to Ramat Eshkol.

For many, the garin are the only ones guaranteeing that half of Lod doesn’t become an Arab-controlled semiautonomous area. Others accuse them of exacerbating tensions. One thing is for certain: They are the only Jewish community that chooses to live in Lod.

“The left-wing media focus on the tensions with our Arab neighbors,” says one member of the garin. “They don’t cover all the things we do for the many communities here, helping families access services and demand things from the local council and government departments they never dreamt they deserve.”

Fida Shehade begs to differ. “We don’t have to be good friends, just have a dialogue. But there wasn’t this type of hatred before the garin came along. I meet them at city-planning committees, and they’re the ones who know as much as I do as a city planner, but they’re not aware of the privileges they have as the most politically connected group here.”

Most people I spoke to in Lod after the election, both Jews and Arabs, were pretty certain that another round of rioting, like the one last May, wouldn’t break out. But not necessarily for positive reasons. The hatred and tension haven’t gone away. But the police and Shin Bet won’t be caught unprepared again. Mayhem in such a central part of the country can’t be allowed to happen.

But, surprisingly perhaps, the outlook on both sides is similarly optimistic.

Shehade thinks that ultimately “market forces will decide.” Since “neither community is going to evaporate,” Lod will eventually become lucrative enough for both sides to share and enjoy its location.

“Better life and better conditions will create security,” says Dreyfuss, one of the leaders of the garin. “New residents of higher class will come, also Arabs. Those are the powers of the market. And they will have what to lose here, culture, community centers, mosques, and schools. They won’t leave and neither will we. I always say that Jews should learn love of the land from the Arabs. Jews have left Lod. But an Arab who was born in Lod dies in Lod.”