Eight years ago, I was wrapping up a reporting trip to eastern Ukraine, where I’d spent a few days traversing the Ukrainian and separatist pockets of the Donbas. Two days before my arrival, the airport of Donetsk was destroyed in the fighting. Rather than give up on the trip, I took a sleeper train from Kyiv.

That turned out to be a bad idea. When the train was stopped for five hours in a forest because of suspected explosives on the tracks, the rabbi of Mariupol, Mendy Cohen, sent his driver to rescue me from the stranded train.

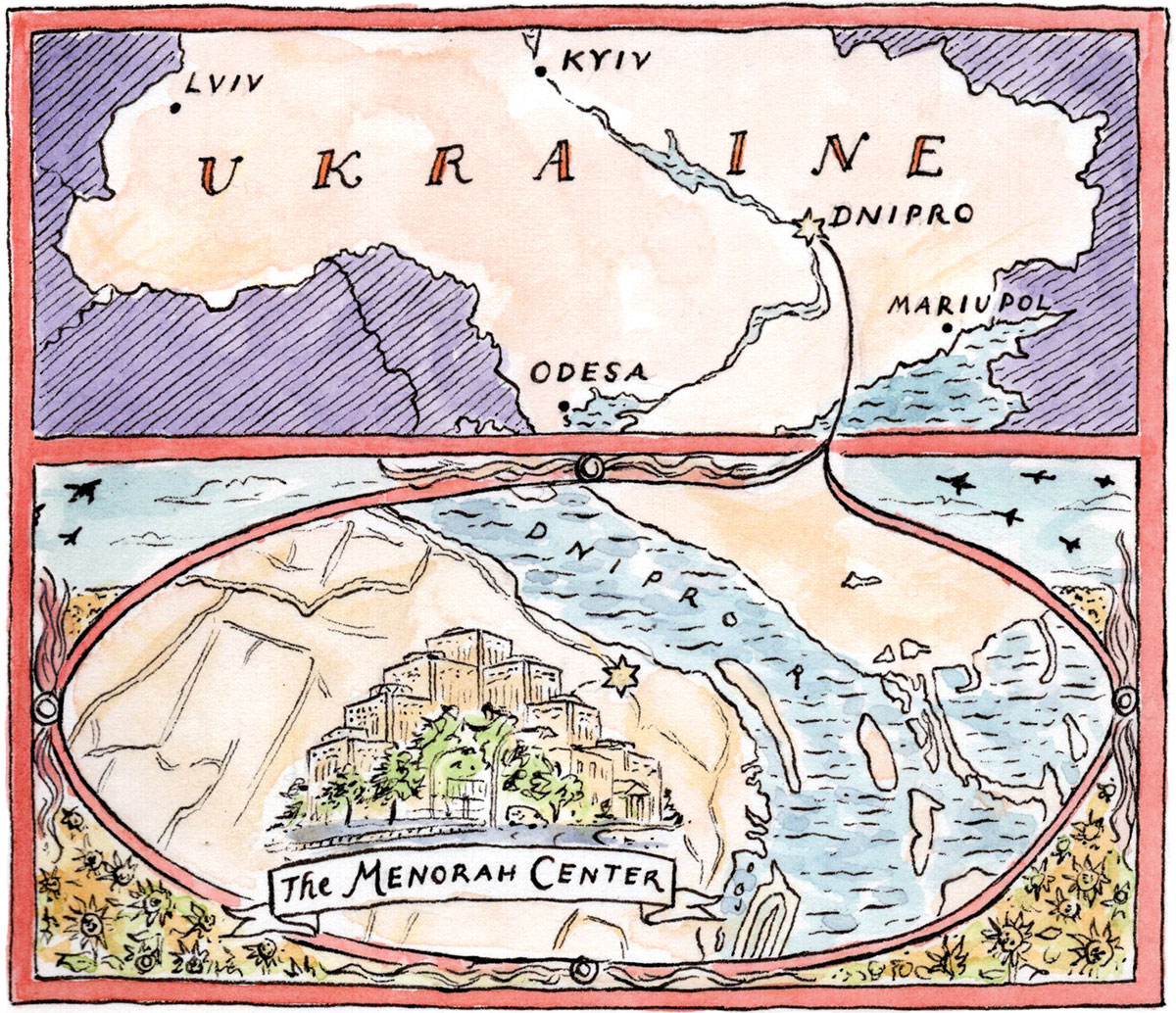

After an eventful few days, I needed a way back to Kyiv and home. The only route was a six-hour drive through back roads, to what was then still called Dnipropetrovs’k — it was officially renamed Dnipro in 2016 — the only city in eastern Ukraine with a functioning airport and flights to Kyiv. My most trusted contact in Ukraine told me, “When you get to Dnipro, stay overnight in the Jewish hotel.” I thought he was joking. “No, seriously, you won’t regret it,” he insisted, and I made the booking, despite my misgivings and mental images of a spartan establishment smelling of fried onions.

I fell asleep on the long drive to Dnipro. When the driver woke me up at our destination, I managed to drag myself and my bags out of the car and asked him where the Jewish hotel was.

“Right behind you.”

I still couldn’t see it.

“It’s right there,” he repeated and drove off, leaving me agitated at being abandoned in the cold evening, outside of what looked like a massive office block.

I walked into the main lobby, and — not for the last time — blessed my contact. I had just entered the largest, most opulent Jewish Community Center in the world: the Menorah Center, brainchild of Rabbi Shmuel Kaminetsky and paid for by billionaires Gennadiy Bogolyubov and Igor Kolomoisky, both of whom were born and raised in Soviet-era Dnipro.

The Menorah Center was much more than that. The massive complex hosted a yeshiva, various day schools and kindergartens, Ukraine’s largest library of Jewish books, a kosher supermarket, a medical center, and a five-star business hotel. It was an ostentatious display of the vast wealth of the Jewish oligarchs of the city. It was also an expression of confidence in the viability of Ukrainian Jewry, a community that had been written off by so many other Jews. My only regret was that I would have to leave for my flight early the next morning, before I had the chance to explore this new Jewish frontier.

Eight years later, with the Russian invasion of Ukraine in its third month, I returned to Dnipro to find out whether Ukrainian Jewry still had a future.

This time, travel through Ukraine was even more difficult. The airspace was closed. And while trains still valiantly operate, they are packed with refugees and the war-wounded. Timetables are erratic. But the three-day drive from the Polish border to Dnipro was instructive.

On the first night, I stopped in Lviv. It was a Friday and I went to the Tsori Gilad Synagogue.

In the elegant 1920s building, which had survived both the Nazi and Soviet periods, there were two men present, refugees from the war-torn east. It wasn’t entirely surprising not to find a minyan for Shabbat evening prayers; after all, the curfew was about to start soon. What was surprising were the mountains of boxes of matzohs and tins of kosher l’pesach noodle soup, which, alongside another massive pile of medical supplies, entirely filled the shul’s anteroom.

During the first two months of the Russia–Ukraine War, synagogues in Lviv, Kyiv and Odesa had become both transit stations for Jewish refugees and logistical hubs for aid operations. In my first visit reporting on the war, back in March, I had met many of those refugees from the war zones in the east. They would briefly stop at one of the synagogues for a hot meal and perhaps a few hours of sleep, still bewildered and unsure whether they planned to continue on to Israel, or wait closer, in neighboring Poland, Romania, or Moldova.

Behind the façade of business as usual at Menorah, they have organized the convoys that have bussed thousands of Jews from the east to safety, often under fire.

On Sunday, after a night in Kyiv, I reached Dnipro, a city of 1 million people, shortly before the curfew. I imagined that the Menorah Center would have undergone the same transformation from synagogue to refugee camp. The hotel at the Menorah Center was closed, so I stayed at another nearby.

I called a local contact to set up a meeting the next morning. “There are three minyanim at Menorah,” he told me. “But don’t worry, I daven at the latest one at 9:30, so you don’t have to get up too early.” I was convinced he was joking. I’d seen what the Ukrainian shuls looked like at times of war, and Dnipro was much closer to the front lines.

Once again, my expectations were confounded. In the center’s main synagogue were about 40 men (and a few women on the side) at morning prayers, as if there wasn’t a war raging nearby. We could have been in a shul anywhere in the world. The center’s kosher restaurants, hospital, and offices were all bustling. Besides one elderly uniformed guard in a booth at the entrance, there wasn’t any noticeable security.

Before I continue, a note about anonymity. The community leadership gave me access and spoke with me freely, on the condition that I would take no photographs, not identify by name any of the members or employees I spoke with, and not specify the locations of any of their operations related to the war. Behind the façade of business as usual at Menorah, they have organized the convoys that have bussed thousands of Jews from the east to safety, often under fire. They have provided these refugees with necessities such as food, clothing, and all the other basics of life. And they run a 24-hour hotline and operations room that help locate and extricate elderly relatives from bomb shelters in devastated towns.

“The last thing we need right now is PR for all we’re doing,” one community leader explains. “It’s no longer just a matter of getting a bus driver who is prepared to drive into a bombarded area and use dirt roads to bypass roadblocks. There’s a lot of very delicate negotiations involved on both sides, and we’re not going to jeopardize the rescue operations or our community here in Dnipro.”

There’s no shortage of other Jewish organizations, from Israel and the West, happy to take credit for rescuing Jews. “Most of them have no real involvement or any idea how to operate here,” smiles a veteran member of an Israeli agency who has been working with Jewish communities in Ukraine for three decades. “They couldn’t find Dnipro on a map. But let’s hope they’ll pick up the tab at least, because these operations aren’t cheap, and the local Jewish philanthropists who would usually pay for this without batting an eyelid are all facing bankruptcy.”

Few Jews who weren’t raised in Ukraine are aware of Dnipro’s existence, much less that it’s one of the largest Jewish communities in Europe. In the wider world, it is Odesa and perhaps Kyiv, with their rich histories, that are better known as centers of Jewish life, as are the shrines of fabled rabbis in the towns of Uman and Medzhybizh.

Yet it’s Dnipro that has become the face of Ukrainian Jewry in the post-Soviet era. Of Dnipro’s million residents, community officials believe that as many as 10 percent are Jewish. “But probably a third of the city has some kind of Jewish lineage,” says one of them.

From the late years of the 19th century, when what was then Yekaterinoslav became one of the major industrial centers of the czarist empire, many of the new factories built in the burgeoning city employed the growing Jewish proletariat, offering rare opportunities for professional training denied to them in other cities. Unsurprisingly, it became an early hub of both Russian Zionism and Jewish Communism. In the pogroms that followed the failed 1905 revolution, an armed Jewish self-defense group was active in the city. In 1926, Soviet authorities renamed it “Dnipropetrovs’k,” but the city quickly acquired the nickname of Zhidopetrovs’k — the “Zhido” meaning Jew — which has continued to this day.

On the eve of World War II, more than 100,000 Jews lived in Dnipro; some 18,000 of them were murdered during the German occupation. But most of the city’s population was evacuated in advance to the Urals, and more than three-quarters of the Jews survived, returning in 1943 when the city was liberated. Dnipro then spent the remainder of the Soviet period as a “closed city,” home to the USSR’s missile factories along with a large number of Jewish scientists, engineers, and administrators.

Over seven decades of Soviet rule, the number of synagogues shrank to just one, and all Jewish organizations were gradually shut down by the authorities. But in the dying days of the Soviet Union, shortly before Ukraine’s independence, representatives of what was left of the community contacted the son of the city’s last rabbi, Levi Yitzchak Schneerson, and invited him to come back and fill his father’s position.

That son — Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson — had spent his youth in Yekaterinoslav before leaving for Berlin and later the United States. By the time the invitation came, he was 90 years old. Instead, he sent Rabbi Shmuel Kaminetsky as his emissary. “This is my town,” the rebbe instructed Kaminetsky before he left New York. He also gave Kaminetsky’s wife advice on the best time of year for purchasing potatoes.

The Jewish community center, just like the Jews within it, was the most optimistic place I’d been to in Ukraine since the beginning of the war. But I still didn’t have a clear answer as to whether they had a future.

Kaminetsky has spent the past 32 years charming the newly rich Jewish businessmen of Dnipro and making the city Ukraine’s Jewish powerhouse. He fully realized that most of the city’s Jews, including many children of mixed marriages, would not become active members of an ultra-Orthodox community. He set about working with any nonreligious Jewish organization, local and international, that wanted to operate in the city, hosting them in the community centers he built. At the same time, he took the rebbe’s words to heart and has blocked all Jewish religious streams but Chabad from operating in the city.

Over the years, he built up parallel education networks, ranging from kindergarten to college. One offers a high-level Jewish liberal education (its primary school once claimed to be the biggest Jewish school in Europe), and the other is much smaller and runs along Chabad-Haredi lines, with a program of Torah studies and separation of boys and girls. Kaminetsky is the archetype of the enterprising Chabad shaliach (emissary), building his own institutions while blending himself and his family into the local community and culture.

His headquarters at the Menorah Center started from a desire to build a Holocaust museum. But Kaminetsky thought the community’s focal point should be more forward-looking and pitched the oligarchs Igor Kolomoisky and Gennadiy Bogolyubov on his grand design: the largest Jewish Community Center in the world. It opened in 2012.

For the first 23 years of Ukraine’s independence, the Jewish community largely kept out of politics. The historic experience of Ukrainian nationalism was, to put it mildly, not a positive one for Jews, who were nearly all Russian speakers and didn’t see themselves as Ukrainian.

That changed in 2014. The Maidan revolution of that year ousted a Moscow-friendly president. In retaliation, Vladimir Putin sent in his army, first to annex Crimea and then to support separatists in the Donbas. The Kremlin’s media machine, echoing Soviet propaganda, tried to tar the new Ukrainian government with fascism, neo-Nazism, and antisemitism. But Ukrainian Jews weren’t looking for a Russian protector. They knew that the extent of antisemitism was nowhere near what Putin was claiming. A new generation had grown and prospered in independent and democratic Ukraine, their Jewishness no longer being an obstacle to achieve success.

For the first time, Jews felt fully at home within the Ukrainian national movement. In no place was this more true than in Dnipro, where the new government of Petro Poroshenko appointed Kolomoisky as regional governor. While the neighboring regions of Donetsk and Luhansk were overrun by separatists, all eyes were on Dnipro, the gateway to the east and Ukraine’s industrial heartland. Kolomoisky raised and equipped local militias and promised to pay cash to anyone capturing a separatist, dead or alive.

The outspoken Kolomoisky, who has a shark tank in his office in Dnipro, is not afraid to celebrate both his Jewish and Ukrainian identity. That’s how, in a country that was once synonymous with the worst of the pogroms, nobody was surprised when a Jewish comedian and producer named Volodymyr Zelensky, born in a city just down the road from Dnipro, was elected Ukraine’s president in 2019, his campaign financed by Kolomoisky.

Despite being much closer to the front lines than Lviv or Odesa, Dnipro feels less like a city at war. While much of Ukraine’s economy remains shut down, shopping outlets reopened earlier in Dnipro than in other cities. Up the street from Menorah, construction continues unabated on a new mall owned by a member of the community.

“People here just get on with their work. That doesn’t mean we’re not concerned,” says a member of the community’s board. “Ukraine’s survival depends on reviving the economy, and there are billions of dollars’ worth of goods stuck in this city that can’t be exported because of the Russian blockade.”

The board member beckons at two men drinking coffee in one of the Menorah restaurants. “Both of them are worth hundreds of millions each, or at least were worth that before February 24. Their families are out of the country, but they haven’t evacuated because they need to keep an eye on business here. And they could be wiped out in a few months.”

What about an exit strategy? “A lot of members of the community have Israeli citizenship as well,” says one of the administrators at Menorah. “Those who don’t will be making sure they do as soon as possible. In the last few years, many people from Dnipro who had emigrated to Israel came back. Prices were cheaper, the weather is nicer, and anyone who was born here misses the sight of the Dnieper.”

I left Dnipro for a second time, this time by car, as now the airport is bombed out. The Jewish Community Center, just like the Jews within it, was the most optimistic place I’d been to in Ukraine since the beginning of the war. But I still didn’t have a clear answer as to whether they had a future.

The entire story of the Jewish renaissance in Ukraine over the past 30 years simply doesn’t make sense. It flies in the face of history that so many Jews would remain in a country where, in living memory, their parents and grandparents had suffered so much, from every political direction: czarist, Bolshevik, Nazi, and Ukrainian nationalist. And yet in Dnipro, it somehow does make sense. It’s a city that was built by Jews. A city where Jews are not obsessing over their history, because they’re still busy building it. And where they have no plans on giving up, at least not yet.

I came to Dnipro wondering whether the Jews of Ukraine had a future. It turned out to be the wrong question. The right question is whether Ukraine itself can continue to withstand the Russian onslaught and prevail. If Ukraine has no future other than as a war-torn region of separatist and nationalist enclaves, then there’s not much future for Jews and non-Jews alike. But if Ukraine survives and prospers as an independent nation, the Jews of Ukraine will have contributed greatly to that victory. And they may yet have a bright future as the most exciting Jewish community in Europe.