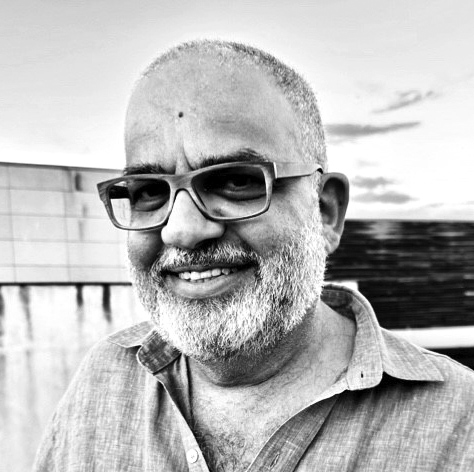

The word faith often makes me cringe, especially when it is uttered or written in English. It feels too concrete, too categoric, to describe the subtle, ethereal relationship between the individual (and especially the artistic) mind and the sublime, or the Divine. The Hebrew emunah, with its lexical flutter toward the word aman (artist), finds itself more palatable on my tongue.

The assonance between faith and art in my native language offers a reflection of the great presence the two have shared in my life and writing. From a very young age, I was drawn to all things religious. One could say that even as a child I heard the soft hum and felt the strong pull of “oceanic feeling,” as the French writer Romain Rolland put it in a famous letter to Sigmund Freud in 1927, describing what he saw as the essence of religious sensibility. But it was not only the lofty, mysterious sense of “eternity” and “being one with the external world as a whole,” to quote Rolland, that drew me into the religious realm — it was the also the rituals, the theatrics, and, most of all, the alluringly arcane world of ancient Jewish text that fascinated me and infused my work with religious symbolism and meaning.

Having grown up in a traditional Jewish home (both my parents immigrated to Israel from Iran and had a pleasant relationship with Judaism, one that was not marred by conflict and rebellion, or the overbearing yoke of Orthodoxy or a strictly halakhic lifestyle), I had the privilege of living between the worlds: receiving modern, secular education while having access to the warmth, depth, and beauty of the Jewish tradition. The synagogue, for example, was not part of our everyday routine, but it was by no means an alien place for me growing up. We went to synagogue on occasion, often crossing Jerusalem and visiting the old neighborhood where our community, the hidden Jews of Mashad, Iran, first settled upon arriving in Jerusalem in the late 19th and early 20th century.

This long march, which I now view as a form of unofficial pilgrimage, was part of the experience. We would leave the modern, secular part of the city where I was raised and venture into the old, religious sections where none of my nonreligious friends at school ever set foot. Everything looked and felt different there. It was as if even the light and air were other than those of the modern quarters. Long-bearded, pious old men shuffled along the dusty sides of the road; young Hasidic men stood tall with their crowns of fur and long, exotic-looking robes; old women threw breadcrumbs for the birds as an act of chesed (loving-kindness) that was meant to evoke the divine midat ha-rachamim (the attribute of mercy), the kind and forgiving element of God’s presence in the world. At times we cheated, driving halfway on Shabbat, finding a hidden spot, leaving the car in haste, quickly donning the kippot that were neatly folded in our pockets, and pretending to fit perfectly into the Orthodox surroundings. This added a certain twist of mischief to the experience, a slight sense of guilt that was not altogether unpleasant, teaching me that religious life does not have to be so earnest, that it can also be playful, and that a touch of sin can spice up a religious experience and even enhance it. In hindsight, I am sure that everybody around us knew about our little antic, and that this almost-comedic charade was part of the social norms of the time — norms that were so much more fluid and organic than nowadays, when the boundaries between religious and secular have become overly defined and almost impassable, a character of political tribes. I’ve realized that this whimsicality, this fluidity, enabled me to play around with religious themes in my writing, freeing me to take artistic liberties while also preserving the sense of awe and yearning that is its base. It is an abundant flow in the varieties of faithful experience, to make a bastard of William James.

But it wasn’t only the journey to the synagogue that imprinted itself in my young mind. My early encounters with the siddur and the machzor were also formative for me. The language — ancient, regal, glowing with beauty and authority — won me over completely. For a young boy who was hypersensitive to the nuances of language, this exposure was life-changing. To this day, in my writing, I find myself drawn to both the modern and ancient layers of the Hebrew — and these layers are heavily hued in religious colors. As in my childhood, I still savor the friction between the modern vocabulary and syntax and its ancient ancestors, the biblical and rabbinic languages, and bring that friction to my work. I also still enjoy the religious — and I mean religious, not “spiritual,” or “transcendental,” or any other laundered, noncommittal term used by people to bypass the fence of organized religion, its symbolic universe, and its demands from the individual — tension and the creative conflict it creates between the text and the often secularized consciousness of the reader. (You might say those who prefer the more sanitized terms risk confusing the fence and the garden, and they should be so lucky to take the risk.)

The confused tension is a common motif in my writing. It came to its peak in my novel The Ruined House (masterfully translated to English by Hillel Halkin and published in the United States in 2017 by HarperCollins) when the unsuspecting protagonist, Professor Andrew Cohen, a secular Jew and a leading expert on contemporary culture, is visited (or seized) by a string of visions taking him back into the depths of Jewish memory, all the way to the Holy Temple in Jerusalem where his ancestors served as members of the priestly clan. Poor Professor Cohen — who is probably the least likely candidate for a sudden, unwarranted, ancient Jewish epiphany — all but collapses under the burden of this strange religious eruption and the suppressed collective memories it brings back.

The fertile dialogue with faith, religion, and Judaism is very present not only in my writing but also in my personal and family life. It was very important for me to live a Jewish life and raise my daughters to be “thickly” Jewish. Reflecting on my religious and cultural choices, I now realize that I created a certain split: I preserved the warm, loving, traditional Jewish environment that I grew up with in my homelife — and allocated the dark, edgy, and dangerous elements of religion to my writing. As a writer, I prefer my metaphors and images to stick to their role — fertilizing and expanding the human and Jewish imagination — rather than detach themselves from the page (or screen) and become too concrete and realistic. I love listening to the distant, soft hum of the oceanic feeling but know that it is much more dangerous for those from much more stressful religious backgrounds who must struggle with the waves of this vast ocean. I therefore feel blessed to have been taught to swim.