The boatman cuts his outboard motor and the rusty launch drifts with the sluggish current of the Suriname River. Try as I might, even with the help of two Parbo Biers, I can’t conjure up a Jewish community along these green banks — much less a realm of Jewish autonomy where Shabbat-keeping plantation owners held sway over the rainforest.

I’ve been to the oldest as well as some of the newest shuls in the world across six continents. I’ve found traces of them where they’ve ceased to exist. You don’t have to tell me that Jews come in all shapes and colors. But somehow, this doesn’t add up: Jews overseeing slaves, carving out fields in the New World jungle, producing sugar to be sent back to Europe, and, on Fridays, taking their boats to gather in prayer at their regional capital for Shabbat.

It sounds like science fiction. But back on dry land, in two cemeteries almost swallowed up by the forest, rows and rows of dark marble slabs with names and Torah quotations carved in Hebrew letters prove that Jodensavanne — Dutch for “Jewish savanna” — was real.

It’s an unknown slice of Jewish history — one in which the Jews banished from Spain and Portugal made their way in the thousands to South America and established an independent Jewish commonwealth on the banks of one of its wide rivers. A haven for a persecuted nation. A Jewish state, almost 300 years before Israel.

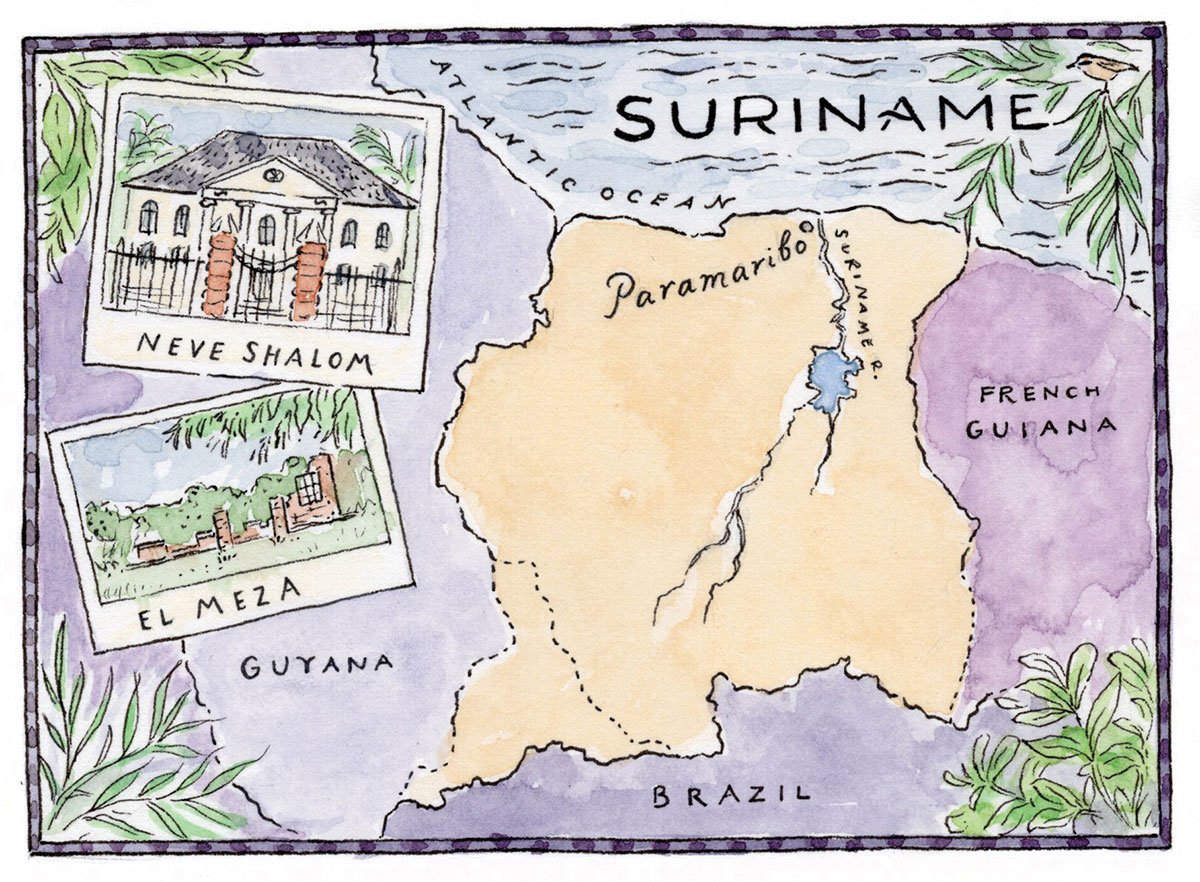

Over a century or so, it prospered, struggled, and was abandoned. Instead of becoming a new and thriving Zion, Suriname, which gained its independence from the Netherlands only in 1975, is today the smallest country in South America and also one of its poorest. The tiny Jewish community, the oldest in the Americas, barely maintains its sole remaining shul in Paramaribo, the capital. Meanwhile, downriver, a small group of archaeologists is working to uncover and preserve what remains.

I visited Suriname in early September, a month before the Hamas attack. I had been invited to join a small archaeological delegation of the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA); they had been asked by the Jodensavanne Foundation, with the backing of the Surinamese government and the funding of the Inter-American Development Bank, to carry out a survey and help prepare a preservation plan.

Joining Israeli archaeologists on a jungle dig 6,000 miles away sounded so fantastical that I immediately said yes. Now, of course, revisiting my notes is surreal: Shortly after my trip, IAA archaeologists were in the headlines for their work on devastated kibbutzim, helping pathologists sift through burnt-out ruins for any trace that could help determine whether those missing were dead or might still be alive, captive in Gaza.

And yet, the questions that came to mind, which I jotted in the margins of my notebook, are suddenly more relevant than ever. What does a Jewish community need in order to survive and thrive in hostile conditions? What kind of support must it have from Jews elsewhere? What level of coexistence with the neighboring cultures and communities is necessary for self-preservation?

Like the other Jews who arrived in America in the centuries after Columbus, the Jews of Suriname descended from Jews banished from Spain and then Portugal. They settled first in the West Indies, Brazil, and Guiana, but Catholic persecution continued there. Suriname, however, was under Anglican English rule, and in 1656, Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell overturned Edward I’s 1290 expulsion of the Jews. This policy extended to the colonies; in Suriname, Jews were granted equal rights with other colonists in 1665. Those rights remained in effect after the English handed Suriname to the Dutch two years later in exchange for New Amsterdam, which they renamed New York.

The Jewish families arriving in this new land brought experience growing sugarcane and refining it into the sugar, much sought after in Europe, that became the colony’s main source of revenue. There are records by the early-18th century of at least 115 Jewish plantations — more than half of all those in Suriname — extending upriver over hundreds of square miles. Slaves, mostly brought from Africa by the Dutch West India Company, worked the plantations. The Jewish community was also in charge of the militia that protected the plantations and the new capital at the river mouth from slave uprisings and indigenous Amerindian tribes.

For roughly a century, this Jewish colony was the only place in the world where Jews enjoyed self-rule between the downfall of the Hasmonean kingdom in the second century and Israel’s independence in 1948.

But after a few decades of prosperity, the community began to decline. French corsairs overwhelmed their defenses and stole huge quantities of sugar. New techniques of producing sugar from beets made their cash crop unviable, and alternatives proved less profitable. The soil was depleted, but applications for new plantations were declined. Slave revolts also took their toll. Families gradually began abandoning the plantations, some moving to Paramaribo, others emigrating to North America. A fire in 1832 destroyed some of the buildings in the main village, and the few remaining families left. Over the next century and a half, the Jewish plantations were reclaimed by the rainforest.

Today, the center of the main village has been cleared of trees, and the foundations of two buildings, the shul and the adjacent home of the El Meza family, have been excavated. Some of the shul’s walls have been partially restored, but there is little to suggest its original use, other than an entrance on each side, symbolizing Abraham’s tent, and a brick platform on the eastern wall, where an ark once stood.

The floor has been covered with white sand, a tradition in the early synagogues of the Caribbean. A team of young local archaeologists works on the El Meza home and its outside cookhouse. It is like similar cookhouses attached to early colonial homes in other parts of Suriname, but for one detail: It has two ovens instead of one. Dairy and meat? Or perhaps the increased capacity is a sign of another halakhic feature of life in the village. If the community really was as observant as the records maintain, it would have meant spending entire Shabbats and holidays together in the main village, because most families lived miles upriver, boats their only mode of transport. The double oven at the cookhouse next to the shul would have allowed multiple families to keep hot their Shabbat lunches of hamin or dafina, the versions of cholent that Jews originally from Spain would prepare. Or perhaps it was pom, a dish of chicken or meat and arrowleaf elephant ear root, believed to be the cholent of Surinamese Jews and today a staple of the country’s cuisine.

There is plenty of physical evidence in the foundations of the El Meza house. Hundreds of shards of kitchenware from Staffordshire in England and Delft in Holland, as well as a Chinese porcelain teacup and a serving platter with a Magen David, attest both to the splendor of the Shabbat meals and to how this far-flung colony traded with the world.

The ships coming over from Europe to take on loads of sugar didn’t just carry Old World crockery. The community wanted slabs of black marble, too. In the next clearing, the slabs still lie, rows of elegantly carved gravestones. Paradoxically, this is where the story of Jodensavanne really comes to life. Four hundred sixty-two markers of Jews who died between 1685 and 1873 have been found in the main cemetery. There are over a hundred more at an older cemetery a couple of kilometers upriver. They are similar to graves from the corresponding period in the Jewish cemetery in Amsterdam. It isn’t clear whether they were ordered after death, engraved back in Europe, and then shipped over the Atlantic, or whether there was an expert engraver in Jodensavanne.

What is clear is that whoever drafted the inscriptions possessed deep Torah knowledge. Many gravestones are inscribed with a Torah verse that corresponds to the circumstances of the person’s death, and whose gematria — the numeric value of the verse’s Hebrew letters — matches the Hebrew year in which he died. A joyous verse for someone who lived to a ripe old age, a woeful one for someone who died in her prime or younger: There are many of those. This was a literate community — many of the inscriptions include original Hebrew poems describing the good deeds of the deceased and lamenting their passing. At the foot of the slab are drawings — the tools of the trade of architects and doctors, a mohel bending down to perform a circumcision. Many graves of Kohanim are marked with palms spread in the priestly benediction. And for those who died young, there are thorny rose bushes or cut-down trees.

Abraham Meiram, a wealthy businessman who died in 1720, is honored with the title of Gvir (other honorifics include Hacham) and is said to have owned the “Field of Efron,” like his biblical namesake. And his grave, like those of the more devout members of the community, is inscribed only in Hebrew. Others combine Hebrew and Ladino, along with Jewish and Gregorian dates. Two adjacent graves — of Emmanuel Pereyra, who died in 1738, and David Rodrigues Monstanto, who died the next year — share the same terrible quote from Psalms: “O Lord God, to whom vengeance belongs. O God to whom vengeance belongs, shine forth!” Below, in Spanish, are the identical circumstances of their deaths: “Killed by the uprising negroes.”

I arrived in Suriname expecting that the centrality of slavery to the story of the Jewish plantations would be a big, sensitive issue. But while the presence and number of slaves who lived on the plantations was noted on a few of the signs around the rather austere information center, it barely came up. It took me a few days to realize that such a small, young nation, barely 20 years after a civil war and still struggling to build a viable economy, has other priorities. Every strand of their national identity is too valuable to cancel. In a country whose population is such a mix of ethnicities — the descendants of slaves, indigenous Amerindian groups, and European colonists, as well as major Indonesian, Indian, and Chinese communities whose ancestors arrived as indentured laborers — Jews, barely present physically, are understood as an important part of Suriname’s history.

Why did the Jewish community not try adding to its number in order to survive? There are records of individual conversions performed by some of the members of Jodensavanne, but nothing on a scale that would have changed the community’s trajectory. No doubt, the aversion of rabbinical Judaism to proselytizing and the distance from the Amsterdam Beth Din that served Jodensavanne played a role. And yet, there were slaves and the descendants of slaves who wanted to be Jewish or considered themselves as such, especially those descended from female slaves impregnated by Jews. In the late-19th century, when the bulk of the community had moved to Paramaribo, the “black Jews” founded their own shul, Darhe Jesarim, in the capital.

It is also very likely that this particular Beth Din — which issued its cherem(excommunication) against Baruch Spinoza in 1656, just when Jews had started to arrive in Suriname, and has not lifted it since — wouldn’t have countenanced large-scale conversions of slaves and the unrecognized children of plantation owners. But there is also no sign that the Jews of Jodensavanne were eager to use conversion to increase their numbers.

In any case, many non-Jews in today’s Suriname take great pride in their Jewish roots. Harrold Sijlbing, a conservationist and the current chairman of the Jodensavanne Foundation, stands next to the grave of his ancestor David Cohen Nassy, one of the earliest leaders of Jodensavanne more than 350 years ago. “The story of what Nassy and his family went through until they arrived in Suriname is important to me. At the same time, I’m very mindful that he was the owner of the slave-woman I am also descended from. This is what makes up our Surinamese identity.” Jovan Samson, a young Surinamese archaeologist directing the new excavations of the El Meza house, helped by groups of high-school volunteers, says he is of part-Jewish ancestry as well. “I am a descendant both of the Jews and the Amerindians who lived here,” he says. “I’m now discovering here my own story.”

“If the community at Jodensavanne was interested in converting people to Judaism, there would have been a huge demand,” says Sijlbing. “When the Moravian church began the first serious missionary work here, everyone became Moravians. But the Jews were here long before the Moravians. If the Jews had been prepared to convert more people, Suriname would probably be a Jewish state today.”

Would that have been a good thing? Surely, having a Jewish state anywhere is good for Jews everywhere. Reinforcements could have been sent to preserve the only example of Jewish autonomy in the world. A Beth Din might have ruled that they could fast-track conversions to help tide them over economic hardships. As Jews fled the persecutions and pogroms of Eastern Europe, might some have been enticed to Suriname?

As the last of the early Jewish communities in South America neared its end, Jewish immigration to what would become the greatest community in the history of the Jewish Diaspora was gathering pace. Setting sail from the Baltic ports, the Jews escaping the Pale of Settlement were all heading for New York. Looking back, it seems inevitable. We are essentially an urban nation. Restore us to Zion — or at least to Manhattan. A Jewish commonwealth in the rainforest belongs to an alternative reality.

One place where I detected no enthusiasm for excavating and preserving Jodensavanne was in the tiny Jewish community of Paramaribo. There were once three shuls in the capital; now there is one. The shul of the black Jews was destroyed and built over in the early-20th century when some of its members converted officially and were accepted by the two other shuls. Zedek ve’Shalom, built in 1736 for the Sephardi families who moved to the growing city from Jodensavanne, is still owned by the community, but it merged with the other remaining shul at the end of the last century.

What is left of Jewish life in Paramaribo centers around Neve Shalom, built in 1835 by Ashkenazi Jewish traders who never ventured farther inland. It is kept going by the income from Zedek ve’Shalom’s building, now rented out to an IT company. All of its furnishings were dismantled and reassembled in Jerusalem, as part of the Israel Museum’s collection of synagogues from around the world. Ironically, there was no shortage of Jewish philanthropists prepared to finance the shul’s preservation in Jerusalem.

Today, there are an estimated 150 Jews in Paramaribo. Ninety are members of the community, half of them over 60. It’s been a decade since a wedding or bar mitzvah took place here. Lilly Duym, the community’s vice president and driving force, gives our delegation a tour of the ornate synagogue. It is in surprisingly good shape. Its white sand is fresh. The tiny museum contains numerous paintings and documents that record life in Jodensavanne, as well as religious artifacts that were used there. Some older Torah scrolls remain in the ark, although they are too mildewed to be read from during the Shabbat service.

But as eager as Lilly is to tell of her work keeping the community alive, she becomes reticent when talk turns to the preservation work in Jodensavanne. Her family, the Abravanels, arrived there 350 years ago, but her life has been dedicated to preserving the community in Paramaribo — including the heart-breaking decision to close Zedek ve’Shalom, where her family worshiped for nearly two centuries, and ship its contents to Jerusalem.

“The government here wants to make Jodensavanne into a national site,” a community member whispers to me. “They hope it will attract investment. They’re less interested in helping us preserve Jewish life right here, where the Jews are.” “It’s a pity that no one from the Jewish community is on the board of the Jodensavanne Foundation,” says Stephen Fokké, a senior civil servant in the Education Ministry and the energetic secretary of the foundation, somewhat cryptically. It seems that in a country of meager resources, there’s room for only one Jewish heritage project, and it’s not the one where actual Jews are currently living.

A few days after our visit, UNESCO recognized Jodensavanne as a site of Outstanding Universal Value. Will this help the Surinamese government, the Jodensavanne Foundation, and the local indigenous tribes to preserve the site and make it a viable tourist attraction? I’m not sure. I doubt we’re about to see repeat visits by Israeli archaeologists and Jewish-American groups on bar mitzvah trips to help with the excavation and preservation. The Jewish world failed to come to Jodensavanne’s aid 200 years ago, when it still offered the slender prospect of a self-ruling Jewish outpost in a hostile world, and it has other, burning priorities today.

But whether the homes and plantations are revealed and restored or remain hidden beneath the trees, Jodensavanne should feature in our collective Jewish memory. Today, it is an urgent reminder that maintaining Jewish autonomy has never been an easy task, which is why autonomous Jewish communities have been so rare in history. To guarantee their viability, they must adapt to changing times. But above all, self-sustainment is never enough. If there is to be Jewish autonomy anywhere, it needs the support of Jews everywhere.