This past July, a curious photograph began circulating on social media. The photograph was of Ayman Odeh — leader of the Knesset’s Joint Arab List — holding a book in the Knesset chamber. Looking closely, you can see that Odeh is thumbing through a volume of the Talmud, prompting the photographer to wonder, according to a reporter: “Who will be Ayman Odeh’s chavruta?”

Amusing and ironic as the photograph seemed to many, there is something fitting about an Arab (or any) member of Knesset coming across such a book in the very room that most represents Jewish sovereignty. The Talmud and books in general have long played a central role in Jewish life, learning, and leadership.

Ever since the widespread proliferation of books began in the 15th century, Jewish culture and book culture have heavily overlapped. Books, and the manuscripts and scrolls that preceded them, have long been technologies of transmission in Judaism, communicating the great ideas and debates of Jewish heritage.

But books are more than that. For the People of the Book, they have always been a quintessential and enduring technology for community-building and, perhaps less intuitively, fully fledged members of the communities they help to build. When Jews are persecuted, so are their books. When Jews thrive, so do their books. They are fellow travelers on the epic journey of Jewish civilization.

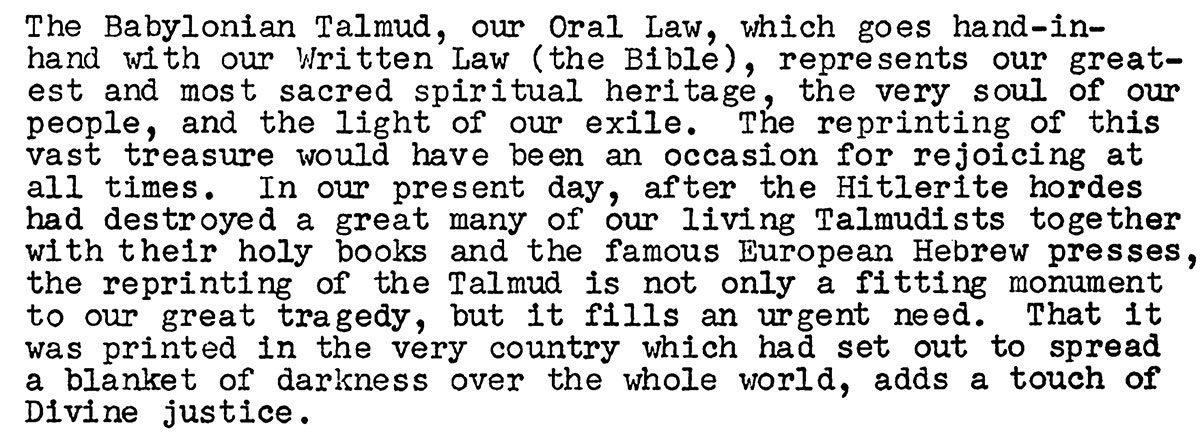

In 1946, a quarter-million survivors of Hitler’s genocide found themselves living in Displaced Persons (DP) camps across Europe. All along the spectrum of religious observance, many who had grown up in Jewishly literate homes began to clamor for the Jewish books that had been at the center of their lives before the war. Chief among these books was the Talmud, the primary text of Jewish study for centuries. This longing is reflected most beautifully in Elie Wiesel’s 1994 memoir, All Rivers Run to the Sea:

Most of all I needed to find my way again, guided by one certainty. However much the world had changed, the Talmudic universe was still the same. No enemy could silence the disputes between Shammai and Hillel, Abayye and Rava.

Many survivors were, like Wiesel, eager to get back to the warm familiarity of Talmud study. There was only one problem: No complete sets of Talmud could be found in what was, until recently, Nazi-occupied Europe. As historian Gerd Korman explains, “in post-war Europe complete sets were hard to find because in the previous ten years the Talmud had been hunted as of yore, in the centuries when, as an embodiment of heresy, Christians had burned thousands of volumes at the stake.” How goes the Jewish book, so go the Jews.

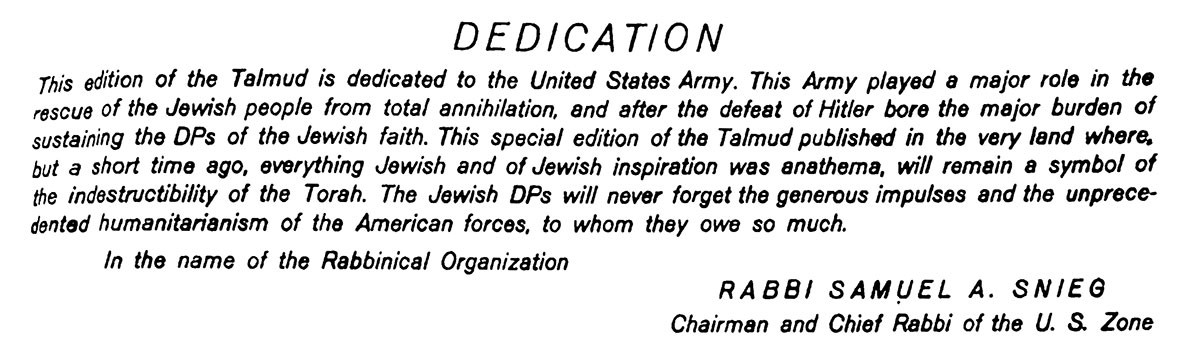

In order to remedy this situation, a group of rabbis — including Abraham Kalmanowitz, Samuel Rose, and, most important, Samuel Snieg, a survivor of Dachau and the Orthodox Chief Rabbi of the American zone of Allied-occupied Germany, had an inspired, audacious idea: to print “an entire Talmud . . . in the land that had tried to destroy Jewish life forever.” Snieg and Philip Bernstein, a Reform rabbi and Army adviser, sought the support of General Joseph T. McNarney, commander-in-chief of United States Armed Forces in Europe. In pleading their case, the two rabbis noted the historic potential of this project. As Korman observes in his 1984 article on this dramatic story: “No Gentile ruler had decided ever before to print and publish a Talmud for the Jews. It would be a distinctly American event, for it is impossible to imagine a European commander in 1946 doing what McNarney did.”

It took more than a year for the U.S. government to provide the necessary paper, which was in short supply, to print these Talmuds. Eventually, the U.S. Army printed 50 full sets of the Talmud at a Heidelberg printing plant that had formerly produced Nazi propaganda. The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) funded the printing of several hundred more. These came to be known as the Survivors’ Talmud and contained a most moving dedication on the inside:

The sets found their way across Europe, Africa, the United States, and, of course, Israel, where the yeshivot of Europe — with names like Telz, Mir, and Lublin — were reconstituting in the fledgling state. Upon receiving his own copy in 1951, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the Lubavitcher Rebbe, wrote the following letter to the JDC’s Moses Leavitt:

In their indefatigable efforts to print the Talmud, Rabbis Snieg and Bernstein, not to mention their partners at the JDC, enacted a basic Jewish precept first spelled out in the Torah (Deuteronomy 31:19): “Therefore, write down this poem and teach it to the people of Israel; put it in their mouths, in order that this poem may be My witness against the people of Israel.” The rabbis of the Talmud interpret this verse as a literal obligation on every Jew to write a Torah scroll. If unable to write one, a person should buy one, or alternatively participate in its writing in some way, including by writing a single letter.

Commentators over the generations developed this precept, extending it beyond the creation and purchase of Torah scrolls to the purchasing of any Jewish books. Other texts bear this out, including the Mishnah in Pirkei Avot (1:6): “Joshua ben Perahiah used to say: Appoint for thyself a teacher, and acquire for thyself a friend and judge all men with the scale weighted in his favor.” Predating Thomas Carlyle’s “My books are my friends that never fail me” by at least seven centuries, Rashi, the 11th-century commentator, interprets this rabbinic adage this way: “‘Acquire for yourself a friend.’ You could read this as books, or you could read this as literally ‘friend.’”

One detects in Rashi’s comment a preference for the figurative interpretation in this case, and it might very well have been the inspiration for the following statement written a century later by Rabbi Yehuda ibn Tibbon in an ethical will to his son Samuel: “My son! Make your books your companions.”

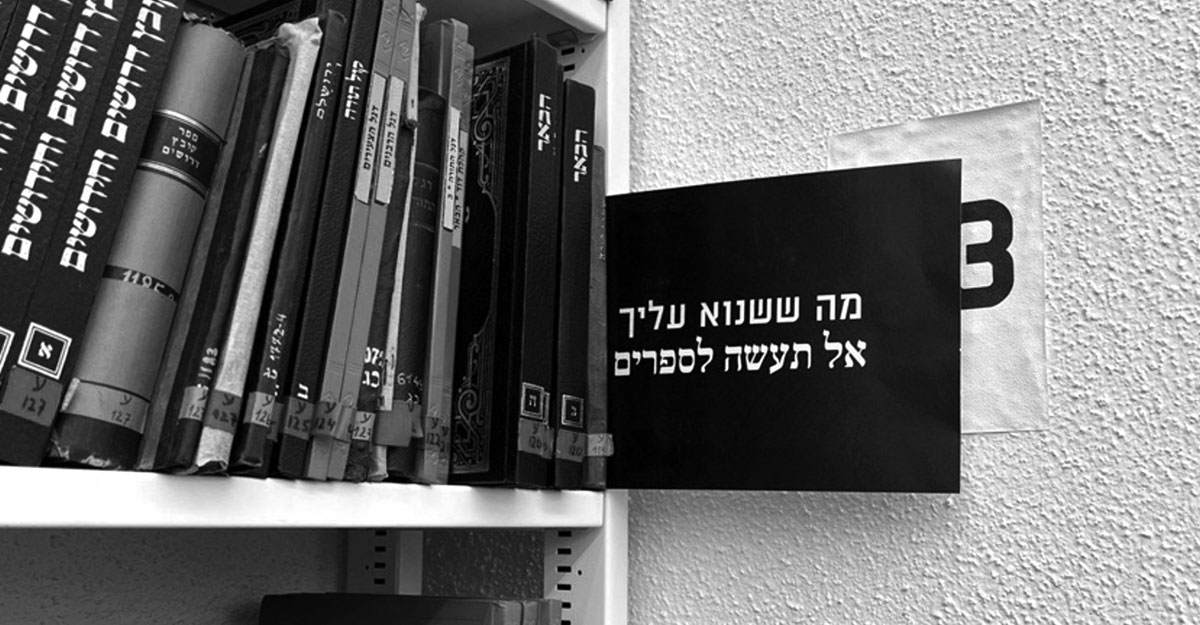

And more recently, in an instructive homage to Hillel’s famous ethical Talmudic aphorism “What is hateful to you, do not do to others,” a bookshelf marker at a Jewish library was spotted by tweeter @YehudahMaccabi offering the following revision: “What is hateful to you, do not do to books.”

Jews have sensed the life in books from the first centuries b.c.e. to the present, a near personification that might be the Jews’ distinguishing feature. It is exactly what Harvard scholar Harry Austryn Wolfson intended when he responded to a colleague who asked him “Why do you Jews think you are so special?” with the memorable answer: “As far as I know, we are the only people who, when we drop a book on the floor, we pick it up and kiss it.”

Over the centuries, our sages have spilled much ink discussing how books ought to be treated. Can one use a holy book as protection from the sun? Is it disrespectful to lean one book on another while studying? Is one permitted to place a book upside down? If one finds a book in such a position, is one obligated to stand it upright? What kinds of books may be read in a bathroom? Is it forbidden to borrow a book without permission? If books bring us joy, is it appropriate to buy books during periods of Jewish communal mourning? The list goes on.

In the Jewish tradition, books are not merely our friends and companions; they also serve to build friendship and companionship. Take, for example, the following Talmudic passage from Ketubot 50a:

The Sages likewise expounded the verse: “Wealth and riches are in his house, and his charity endures forever” (Psalms 112:3). How can one’s wealth and riches remain in his house while his charity endures forever? . . . One said: This is one who writes scrolls of the Torah, the Prophets, and the Writings, and lends them to others. The books remain in his possession, but others gain from his charity.

What is charity? The Talmud answers: lending books to others.

Write books. Buy books. Lend books. The tradition seems strangely preoccupied with the lifecycle of books. Why?

What emerges from these practices is a mandated bibliophilic marketplace in which books become the currency of community and social cohesion. We find a strikingly explicit example of this in a responsum penned by Rabbi Yitzchak Zilberstein, a contemporary halakhic authority in Israel, who wonders whether one can fulfill his obligation of sending food to others on Purim — to bring joy to them — by sending books instead of food portions.

That books nourish is something that all bibliophiles know, but in this bibliophilic marketplace, sometimes the pleasure is as much in the pursuit as in the acquisition. Rabbi Andy Bachman recently related a personal story on his excellent Substack newsletter about his search for a particular book, Menorat HaMaor (The Illuminated Lamp), by the 14th-century Spanish scholar Rabbi Isaac ben Abraham Aboab. Bachman set out on his bike to various Jewish bookstores in Brooklyn:

My first stop was at Seforim World on 16th Avenue. . . . Alas, it would have to be ordered from the warehouse. It would take a few days. So then I rode over to Eichlers on 13th Avenue but struck out there too.

But I still had fun. Because as a non-Hasidic, non-Orthodox person shopping for Jewish books in Boro Park, I suppose I could feel out of place. Between my bike helmet serving as a yarmulke and clean-shaven look, I do stand out. But a Jew in search of a book is a Jew in search of a book and for the more than 30 years that I have been going to these two booksellers, I am always heartened by the feeling of inclusion, respect, and love for learning that is shared when I show up in search of something.

The Jewish injunctions to write books, buy books, lend books, and gift books reveal a unique — and uniquely Jewish — faith in the power of books. As the observations of Rabbis Zilberstein and Bachman attest, books and Jewish book culture offer more than knowledge. They are, as our tradition teaches, mechanisms for fostering community, unity, and joy — even before they’re opened.

Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, who revolutionized Talmud study with the publication of new editions of the Talmud beginning in the 1960s, was often asked whether the people who buy his Talmuds in fact read them. His response, as recorded in Arthur Kurzweil’s memoir of 25 years of travel with the wise rabbi: “Just having a beautiful Jewish book on the table or on the shelf in one’s home enhances a Jewish home.”

Anyone who has ever been in a Jewish home library, surrounded by volumes with formidable bindings and impressive gold lettering, can attest to this. They affect the atmosphere; they effect the atmosphere. As Leon Wieseltier put it several decades ago: “The spines of books. Books and spines. Books are spines.” Books form the backbone of a Jewish home.

This sentiment is likely what led the Lubavitcher Rebbe in the 1970s to initiate a campaign called Bayit Malei Sefarim (A House Full of Books), encouraging Jewish families to stock their shelves with Jewish texts. For Rabbi Schneerson, better known for his Shabbat candlelighting and tefillin campaigns, the Jewish love affair with the book hinted at what social-science researchers would later confirm and The Guardian would one day report: “Growing up in a house full of books is a major boost to literacy.”

A similar instinct inspired Fanny Goldstein, a Russian Jewish immigrant and librarian at the Boston Public Library’s West End Branch in the 1930s and 1940s. While the Nazis were rounding up the Talmuds of European Jewish communities, Goldstein sought to revive Jewish literacy in the United States, displaying Jewish books for the library’s immigrant-dominated community. Her simple display evolved into Jewish Book Week, which transformed into the Jewish Book Council (JBC) in 1944. Among many other activities to support the ecosystem of Jewish books, JBC continues to support Jewish book celebrations in Jewish communities across the country.

The Jewish philanthropic community has admirably taken up this charge in other ways as well. The Keren Keshet Foundation seeded and supports Shavua Hasefer — an annual, weeklong book festival — in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. During its 25 years of grantmaking, The AVI CHAI Foundation experimented with a variety of book-distribution programs, including sending a basic “Jewish Bookshelf” to Birthright Israel alumni and new Jewish day-school students. And although philanthropist Harold Grinspoon credits Dolly Parton with having inspired PJ Library, which distributes free books to Jewish children and their families around the world, I think it is fair to think of PJ as a worthy twist on Rabbi Schneerson’s House Full of Books, itself a novel expression of our age-old commitment to books as the building blocks of Jewish homes and communities.

That Jewish literacy was and is considered by Jewish philanthropic organizations to be a feature of Jewish welfare is a testament to the community’s commitment to the preservation and proliferation of Jewish books as the communal technology that they are.

Among the great technological innovations of our time is Sefaria, the free online digital library that proudly refers to our texts as “a collective inheritance”:

For thousands of years, our culture, our traditions, and our values have been transmitted through our texts. From an oral tradition to handwritten scrolls to a vast corpus of printed books, each new medium democratized knowledge, and brought more people into the great Jewish conversation. We are the generation charged with shepherding our texts from print to digital in a way that can expand their reach and impact in new and unprecedented ways.

The Jewish digital revolution — Sefaria, AlHatorah, Otzar HaHochma, and more — has transformed Jewish life and learning. But as much as we acknowledge the promise of digital Torah, one can’t help but wonder: Even if I can carry and access more Jewish texts than ever on the tablet in my hand, what might I also be losing in the process?

One thing at risk is the Jewish literary space. In “Voluminous,” a 2012 piece for the New Republic, Leon Wieseltier gave voice to the danger:

The library, like the book, is under assault by the new technologies, which propose to collect and to deliver texts differently, more efficiently, outside of space and in a rush of time. . . . A book is more than a text: even if every book in my library is on Google Books, my library is not on Google Books. A library has a personality, a temperament.

That libraries are an act of self-definition is true both for the libraries of individuals and the libraries of nations — especially the Jewish nation. When Israel’s leaders, most recently Prime Ministers Netanyahu, Bennett, and Lapid, broadcast messages to the country and the world at large, Talmud sets and other Jewish books often sit on the shelves behind them.

No one appears more aware of this than the founder of Sefaria himself, Josh Foer. He is also among the founders of Lehrhaus in Boston, described as “part Jewish tavern, part house of learning.” Given Foer’s connection to Sefaria, you might expect to find iPads along the walls and stacked on tables, making the full spectrum of Jewish literature available to all. But the walls of Lehrhaus are filled with books and portraits of great Jewish authors.

Digital revolution aside, Jews still revel in their oldest technology. In the age of Sefaria, it is quite a wonder that the Codex Sassoon, the world’s oldest intact Hebrew bible, not only fetched a record-breaking $38 million at Sotheby’s but also attracted thousands of spectators to a building on Manhattan’s Upper East Side hoping to glimpse just one of its folios.

The widespread interest is a form of Jewish celebration. The throngs of viewers came to pay homage to this precious artifact, to celebrate its existence and to bask in our rich, collective inheritance. It was not a foregone conclusion that our tradition, manifest in this brilliant book, would make it down to us, today. It was almost as unlikely as Jewish survival itself.

As the paratext of the Survivors’ Talmud recounts:

We all remember well the bitter days . . . in the ghettoes . . . when the evil Nazis would demand that we gather all of our books in one place, in order to destroy them, and the life threatening danger involved in hiding just one Jewish book.

Remembering the books burned on the altar of Jewish history reminds us why we should treasure them today. They have been entrusted to us, and we are beholden to them. Our fates are intertwined and inseparable. Again: How goes the Jewish book, so go the Jews.

How might we tap into these incredible stories, and this recent interest, to inspire greater commitment to membership in the People of the Book?

To today’s philanthropists and leaders and educators, I suggest: Follow in the footsteps of our rabbis — and Fanny Goldstein — and work tirelessly toward the making, reading, gifting, and lending of books. Fund authors to write them. Buy them in bulk and send them to everyone you know (enclose a handwritten note if you really want to hammer home the point), and encourage others to do so as well. Fill your libraries and offices with books. Assign them to your staff and students. Resist the urge to go fully digital.

If we are interested in meeting the new technological age with wisdom and confidence, we need only to consult our friends, our companions — our books. The famous tagline for Patek Philippe, the luxury watch brand, is instructive: “You never actually own a Patek Philippe. You merely look after it for the next generation.” That’s how I think about my volume of the Survivors’ Talmud. I turn to the back of Tractate Avodah Zarah, where the text of Pirkei Avot is tucked away. Joshua ben Perahiah reminds me: Acquire a friend.

And in my hands, I realize, I already have one.