It’s the only kosher shop in town and you can find there every type of Ashkenazi food imaginable, if you can just make sense of the chaos. Men in black are stacking sacks of flour and receiving the delivery of freshly slaughtered meat. The till goes unattended for lengthy periods, but no one is worried about shoplifting. On a little shelf near the entrance lies a pile of shoddily printed Yiddish newspapers with blaring headlines of a distant war on the outskirts of the Russian Empire.

Other men in black are coming in from prayers at the shul next door, exchanging gossip, taking shelter in the entranceway while stopping for a quick morning smoke. A cold wind is blowing in across the mudflats. In the distance, out at sea, cargo ships are moving slowly in the mist. This could be a shtetl on the Baltic shores, in the northern reaches of the czarist Pale of Settlement.

But then the men with their tallis bags and shopping bags filled with milk and cereal pile into their minivans, parked haphazardly between piles of building materials, and drive home past immaculate red brick houses bordering a bleak and beautiful golf course on the Essex coast.

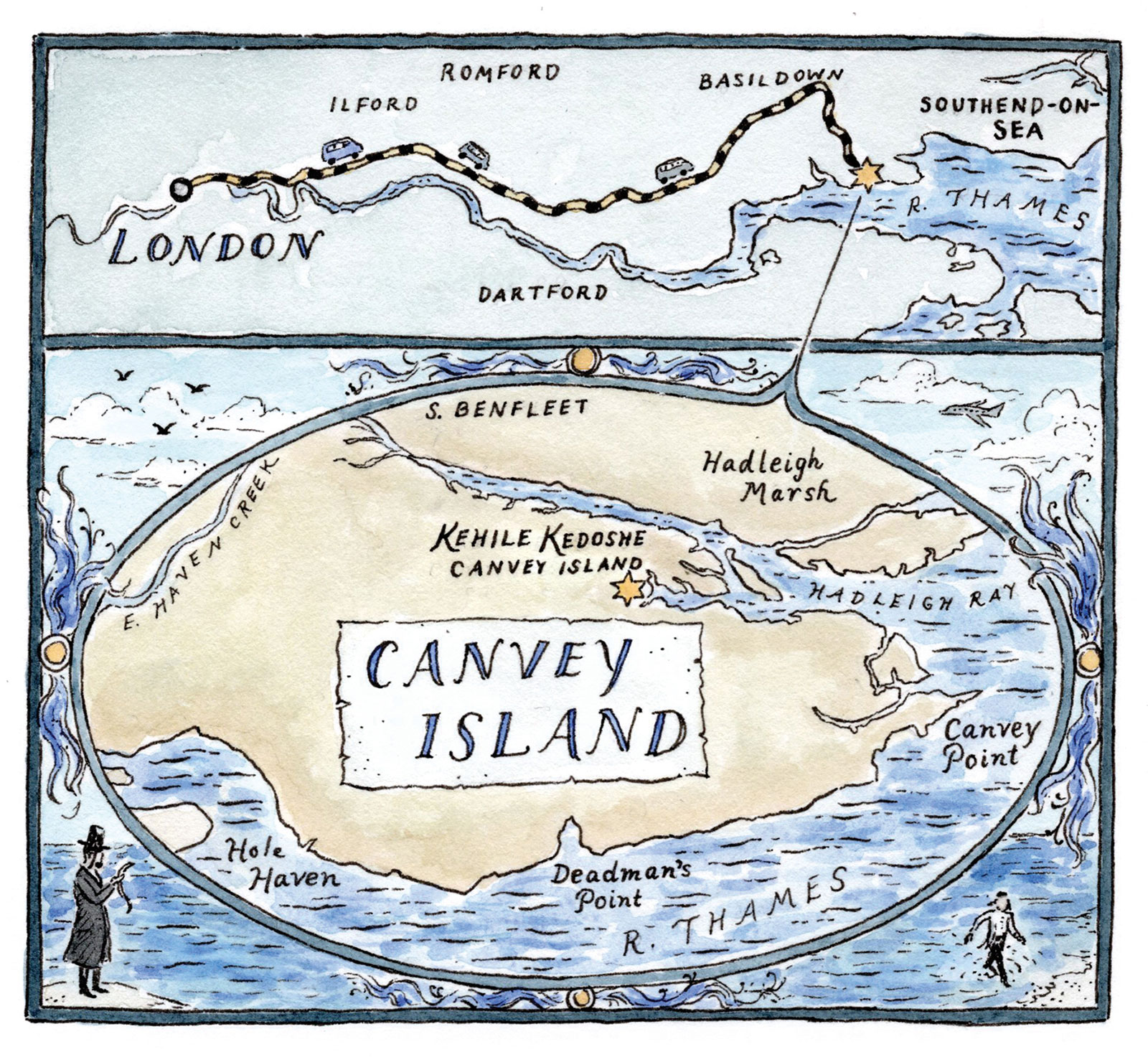

This is the new frontier of the Haredi world. Kehile Kedoshe (holy community) Canvey Island — an autonomous group of a hundred ultra-Orthodox families who, less than six years ago, began escaping the housing crisis of inner-city London, just over an hour’s drive away.

As in other countries with sizable Jewish populations, the Haredi community is the fastest-growing Jewish group, estimated currently at around 60,000, or 20 percent of British Jews. But over the past decades, while they increased in number, they shrank in geography, concentrating in a handful of neighborhoods in north London and Manchester, with one northern outpost around the yeshiva in Gateshead founded in 1929.

This is the first major migration of Haredi Jews to a brand-new location within Britain in nearly a century, when the children of migrants from Eastern Europe began moving from the overcrowded East End of London to the more comfortable suburbs to the north, making way for new waves of immigration to Britain.

And unlike in the United States, where ultra-Orthodox communities have been moving out of New York City to places such as Lakewood, Monsey, Kiryas Joel, and New Square since the 1940s, the Canvey Island community wasn’t created at the behest of a charismatic rabbi. It was the initiative of a few men in their late twenties and thirties.

“We were a group of about seven or eight people, in early 2015, who stayed behind at shul one evening after Ma’ariv and talked about house prices and what we can do,” says Joel Friedman, one of the founding members of the community and the first to purchase his family’s new home in Canvey Island, in February 2016.

Friedman, 37, is a father of seven, a Satmar Hasid, and for want of a better definition, can be best described as a macher — a grassroots activist. He commutes daily back to Stamford Hill in London, where he works as director of public affairs at Interlink and the Pinter Trust, organizations that work to provide public services within the British Haredi community and connect it with local authorities, the media, and the British government. His group spent nearly a year trying to find a location for their new community.

They scoured the area around London, looking for a place that fit their requirements. It would need to be about an hour away, so as to be “not too far, but also not too close, so it could become self-sustainable and not rely on Stamford Hill for everything,” says Friedman. It would need to have a low crime rate, space for building communal institutions, and above all, a ready supply of homes at reasonable prices.

Ultimately, what dominates the new community’s growth is real estate.There is only one cardinal rule of membership—that no one negotiates his own home purchase.

This wasn’t the first attempt at establishing a new Haredi community outside Greater London. Larger and better-financed organizations and groups had tried in the past to build an ultra-Orthodox neighborhood in the new city of Milton Keynes and projects in other places, but there was a reluctance of local authorities to go along with a secluded community, and the Haredim lacked the organizational and financial heft necessary.

Friedman’s group of individuals, without backing, accepted that they would not be capable of creating a separate Haredi neighborhood, but believed they could establish a viable community in an existing place.

On the short list of locations they compiled, Canvey Island stood out for a number of reasons. A bustling seaside resort in the early 20th century, Canvey was nearly destroyed by a major flood in 1953, and the entertainment business never recovered. The absence of nightlife is a plus for an ultra-Orthodox community, and it also means a low crime rate.

The rebuilt Canvey Island appealed in the 1980s to upwardly mobile young families seeking comfortable homes and large gardens outside London. Now, much of the local population consists of retirees looking to sell their four- or five-bedroom houses. But unlike other areas within commuting distance of London, Canvey’s traffic problems, caused by having only one main road out of the island that is usable during high tide, have kept the house prices down.

Though no one there will admit it, the success of Canvey is proof of the resourcefulness of young Haredi Jews who have gotten used to the massive age gap and remoteness of their rabbis.

And yet, despite ticking all the boxes, there was a reluctance, even on the side of the founders, to strike out alone. Friedman became the first to put down a deposit in February 2016. He was followed by six others, encouraged by their surprise success in purchasing the large, derelict building of a closed-down local school and the surrounding grounds, which have served since as the community center, shul, kosher grocery, mikveh, and campus for an entire range of separate boys’ and girls’ schools. All of them are in various states of rebuilding, while in use.

The first seven families agreed to move there together so they would have the nucleus of a community from the start, and on a Thursday evening in July 2016, the first Ma’ariv prayers were held in the shul. “Friends and relatives came to make sure we had minyanim,and the first Shabbos was a bit like a summer camp,” recalls Friedman. More families soon joined, and each one knows their number in the order of arrival. They’re up to 101, though the actual number is 98, as three have left.

So far, every home that has come on the market and that’s within walking distance of the shul has found ready buyers, but the demand, while steady, is still rather low. One or two families are added each month on average, with most newcomers arriving in the summer in between school years. “Despite how crowded it is, many families are psychologically incapable of leaving Stamford Hill,” says Yaakov Yuzevich, a Canvey resident in the past three years, who works in real estate. “It’s as if the river [Hackney Brook, which borders Stamford Hill] is a border they can’t cross. Particularly women, even after they’re married with children, want to be around the corner from their mothers.”

A visit to Stamford Hill back in London demonstrates this very clearly. In the Haredi area, you see rows of crowded terraced buildings with mezuzot, home after home, and a couple of commercial streets with kosher grocers, butchers, restaurants, and Judaica shops. Then you turn a corner and there’s barely a kippah to be seen.

“It’s hard to explain, but some people don’t want to live even five minutes away from their families, even if they can find cheaper homes,” says Friedman.

Ultimately, what dominates the new community’s growth is real estate. There is only one cardinal rule of membership — that no one negotiates his own home purchase. For the community to remain viable, they need the house prices to remain stable, at around their current level, which is less than one-third of what similar-sized houses cost in Stamford Hill.

“It’s an open market, anyone can buy a house, but for us, it’s not an open market, we won’t shoot ourselves in the foot,” insists Friedman. The community has a va’ad — a committee that negotiates the price for potential members. “Someone can come along who has a wealthy father-in-law and offer a higher sum, but we operate on a first-come, first-served policy, with a loophole for people the community needs — for example, a new teacher for one of the schools will go to the front of the queue. Anyone who breaks that rule and buys a house separately won’t be able to use the kehile’s facilities, they won’t be able to daven at our shul, and their children won’t learn at our schools. We’re building this kehile with our blood and sweat, and we want it to remain viable so one day our children can buy homes here as well.”

Inside the shul, there’s a board with all the usual notices on services and events and also a few unique to Canvey — such as the reminder that the ritual times for prayer based on sunrise and sunset are a minute later than in London, due to the eastern location, and instructions how to walk on Shabbat to the closest hospital in Southend-on-Sea, without breaking the halachic injunction of tchum shabbat (which forbids walking outside town).

There’s also a stern notice in Yiddish warning everyone of the grave implications of buying a house independently of the va’ad.

If this sounds coercive, it’s worth bearing in mind that Canvey Island is a Haredi community that exists without a rabbinical leader, though some of its members have semicha (rabbinical ordination) and they employ a dayan who rules on more technical issues of halacha. The Satmar Hasidim are the predominant Haredi sect in Canvey, affiliated with Rabbi Aaron Teitelbaum, who rules his international flock from Kiryas Joel in Orange County, New York (Satmar has been split for 16 years between two brothers, Aaron and Zalman). But Canvey is a general Hasidic community, not an exclusively Satmar one, and the rebbe is a distant figure. In March, Reb Aaron visited Britain but didn’t come to see his followers in Canvey. “We’re much too small and poor for him to visit,” wryly observes one Satmar Hasid, who insists they weren’t disappointed at being left off the rebbe’s itinerary.

Though no one there will admit it, the success of Canvey is proof of the resourcefulness of young Haredi Jews who have gotten used to the massive age gap and remoteness of their rabbis. It’s also proof of the adaptability of Haredi life — that the trend over the past 80 years among Haredi communities everywhere toward living in isolation isn’t irreversible.

How do the Haredi communities continue to sustain themselves, when there is such a gap between ‘infallible’ leaders in their eighties and nineties and a massive young generation that is much more exposed to the outside world than were their parents, who grew up in homes where television and radio were forbidden?

At first sight, the houses in the streets around the shul all look identical, but you can discern very quickly which ones are owned by members of the Jewish community, even before you see the mezuzah on the right-hand-side doorpost. The first sign is the car parked outside. The Hasidic families all have battered minivans. Then there are the bicycles piled around the door and the state of the front gardens.

“Our goyishe neighbors are mainly pensioners who all have lovely tended English gardens, both in front and around the back,” says one of the ultra-Orthodox homeowners. “I’d love to garden as well, but we’ve got less time, as we’re taking care of large families.”

“For me, one of the things I’m most happy about here in Canvey is that my children have got to know and respect their non-Jewish neighbors,” says Avrohom Kaff, owner of the kosher store. “That doesn’t happen in Stamford Hill.”

“My children have learned here not to be afraid of dogs,” says Joel Grossberger, a used-car salesman.

When I ask Haredi parents in Canvey Island whether they’re not concerned about the outside influence on their children of growing up in a less insular environment, they shrug and say that the city has more than enough of its own temptations.

An hour away from multicultural London, Canvey Island remains a bastion of the traditional Tory-voting white English working class, which joined the aspiring home-owning middle class under Margaret Thatcher. In the 2019 general election, it reelected its local member of parliament with the third-highest Conservative majority in Britain. In the 2016 referendum on leaving the European Union, it also had the third-highest vote in favor of leaving. By all accounts, the relationship between the kehile and the local community has been friendly and there is a feeling of kinship between the two groups, who both arrived here to escape crowded London. “One of the local councilors told me that we’ve finally brought diversity to Canvey,” smiles Friedman.

The tension between urbanization and the secluded life of the shtetl existed already back in Eastern Europe and continued in the new Haredi worlds, as many rabbis sought to take their communities out to the suburbs, with varying degrees of success.

Historian David Myers, who has just published American Shtetl: The Making of Kiryas Joel, a Hasidic Village in Upstate New York with his wife Nomi Stolzenberg, says that Canvey is another example of “how the Haredi community settles the need for spiritual purity with the need for affordable housing. It wasn’t just about having splendid isolation. It’s always been present. Very often the primary motivating factor. There’s no such thing as isolation, it’s the illusion of isolation. To create the conditions to succeed and flourish, they need to have these connections with the outside world. They’re not the Amish and they’re not living off the grid.”

One of the most fascinating stories of the Jewish renaissance that followed the desolation of the Holocaust is the rebirth and resurgence of Haredi life: A community that had lost most of its members, its leaders, and its physical center in Eastern Europe, managed to rebuild itself, even surpass its former glory, in nearly every spot on the globe that a determined group of families settled, from Monsey to Manchester to Melbourne.

But the phenomenal birth rates and success in isolation have created a new set of challenges. How do the Haredi communities continue to sustain themselves, when thanks to modern medicine, there is such a gap between “infallible” leaders in their eighties and nineties and a massive young generation that, thanks to the internet and smartphones, is much more exposed to the outside world than were their parents, who grew up in homes where television and radio were forbidden?

Keeping hundreds of thousands of young Haredi men and women with different aspirations and expectations than their parents within the fold will be a mammoth task, even if they can find places for all of them to live and raise families of their own.

In the two largest Jewish communities — Israel and the United States — the response to these challenges by the Haredi leadership has been to try and double down on isolation, a policy that failed miserably in the last two years of the pandemic, when the world couldn’t be kept outside.

The founders of the Canvey Island kehile are from the third post-Holocaust Haredi generation, now coming to the fore in leadership roles. As members of a much smaller but rapidly growing ultra-Orthodox community, they have had to adapt faster on their own initiative and figure out new ways to live and prosper in closer contact with wider society. A hundred families on the Thames estuary may have found the way forward for their global community.